Great Vaishnava Women

An address to members of the International Network of Women and Religion (INWAR) at their headquarters in New York City.

I’ll begin by defining two words: Vaishnava and women. A Vaishnava is a devotee of the Supreme Personality of Godhead, more personally known as Vishnu or Krishna. In India this term is quite common, and there are millions who follow the path of Vaishnavism. Ultimately, Vaishnava refers to the natural state of the soul, since all living beings are constitutionally related to God in a mood of loving devotion.

The second word, although more familiar, is more difficult to define when used with the word Vaishnava. The man/woman dichotomy relates to the body, whereas the “Vaishnava” designation refers to the nature of the soul. In one sense, a Vaishnava is not really a man or a woman, and so reference to “women Vaishnavas” or “male Vaishnavas” is inaccurate.

For the sake of common parlance, however, it is practical—if not downright necessary—to acknowledge the bodily distinctions that exist within the material world. After all, a woman can serve God (i.e., act as a Vaishnava) by having children, for example, whereas a man cannot. So while women and men are spiritually equal, they may serve God in different ways. Worldly differences can thus be acknowledged and should be used in divine service. In this sense, then, we may rightly speak of “women Vaishnavas.”

Women in Vedic Culture

For a clear understanding of Vaishnava women and the activities that led them to greatness, we look to ancient India’s Vedic literature, the spiritual classics upon which Vaishnava dharma rests. In the earliest Vedic texts, we find that the woman was mainly seen as the wife or mother. The emphasis was on her place in the home, and her work was given divine status. Her religious duty was to maintain the spiritual environment of the home and to raise children as devotees of the highest order. This she could do only if her own spiritual practices were strong and if her meditations were profound. Guidelines are given in the scriptures that can assure perfection on this path.

It might be asked why the woman rather than the man was given the service of homemaker. One answer offered by the Vedic texts is that since the child came from her body, she would naturally take very seriously the service of raising the child in God consciousness. She also could not bear to be away from her child—flesh other flesh. The husband had a less difficult time going out—away from the child—and making a living. The wife, in general, felt more comfortable at home. It was natural and pleasing. Both parties, playing their respective roles, served to create a spiritual atmosphere within the household. Especially when they both learned to see their roles as service to Krishna. In this sense, the roles are absolute—the roles they play are equal in that they are merely different ways to serve the Supreme.

The Vedic epic Ramayana explains the social hierarchy that existed within the spiritual home: strinam bharta hi daivatam. That is to say, the husband is the guru for the wife, even as the wife is theory for the child and the spiritual master is the guru for the husband. In other words, in the Vedic household everyone had a spiritual authority, and in this way social sanity was maintained and everyone in the family could progress toward the ultimate goal of life: spiritual realization.

There were, however, exceptions to the traditional roles of men and women, and as we delineate the great Vaishnava women throughout history, we will elucidate upon the ascetic tradition that made clear the spiritual equality between men and women.

It should be noted that the greatest Vaishnava of all time is Srimati Radharani, who is female. She, of course, is also known as a manifestation of the Supreme and so does not really figure into our discussion.

Among the women described in the Vedic literature, the most important for her representation of ideal womanhood is Sitadevi, the wife of Lord Ramacandra. She embodies all of the qualities to be found in the ideal Vedic wife. Although goddesses such as Parvati and Lakshmi-devi, and other heroines from the Vedic literature such as Savitri and Damayanti are also good examples, it is Sita who is particularly remembered as the ideal in conventional Vedic womanhood. Indeed, even today one hears the Indian mother tell her daughter. “Be like Sitadevi.”

Great Women Vaishnavas

Vedic culture gave rise to many great women. In addition to Sitadevi there were the likes of Draupadi, Kunti, and Gandhari. The great women of the Vedic period are often considered prehistorical personalities, many of them gracing the earth more than five thousand years ago. Since that period is now shrouded in antiquity, and since many of the stories surrounding their lives are often confused with mythological tales. I will restrict my discussion to women Vaishnavas within the last five hundred years.

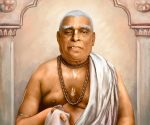

Sachidevi

Sachidevi appeared in Bengal in the mid-fifteenth century. Playing the role of the perfect mother and wife, she was glorified as the mother of Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu and the wife of Jagannatha Mishra. Sri Chaitanya, the founder of Gaudiya Vaishnavism, is a combined manifestation of Radha and Krishna.

Sachidevi was the daughter of a well-known Bengali family that migrated from East Bengal (now Bangladesh) and settled in Navadvipa. Her father, Nilambara Cakravarti was a very influential man because of his knowledge of astrology and the Vedic scriptures.

After marrying Jagannatha Mishra, Sachidevi went through great austerities as a mother. In fact she lost eight female children during successive pregnancies, and she wept in anticipation of further offspring. Sachidevi’s next child was a boy—Vishvarupa, who survived. Some years later, she gave birth to Sri Chaitanya. But while little Nimai (as Chaitanya was called in His youth) was still an infant Vishvarupa renounced the world and became an ascetic. This brought untold regret to Sachi, for now Vishvarupa would no longer bring joy to the Mishra household. He would now wander the countryside, preaching and visiting temples in service to the Lord.

Jagannatha Mishra did not survive the trauma of Vishvarupa’s renunciation. Sachi, however, managed to carry on, and she resolved to raise little Nimai to the best of her ability.

Because of the purity and intensity of her devotion, her aspirations for her last surviving child would be more than fulfilled. As Nimai grew He developed exceptional features, profound scholarship, and a devotional attitude. His concealed divinity began to blossom, as the scriptures had predicted it would.

But Sachi’s domestic happiness was short-lived, for at the age of twenty-four Sri Chaitanya, too, became a renunciant, following in the footsteps of His brother, Vishvarupa. Despite this final blow to her hope of familial bliss, Sachi’s perseverance as a devotee remained unscathed.

Sri Chaitanya, in fact, had asked for His mother’s permission to lead the life of a renunciant in service to God. Although it was difficult for her, she nonetheless relented, the only stipulation being that He make His headquarters in nearby Jagannatha Puri, so she would regularly hear news of His activities.

Although Sri Chaitanya’s renunciation is remembered as a pivotal event in the history of Gaudiya Vaishnavism, Sachidevi’s renunciation is glorified in the annals of Vaishnava history as unbounded. For in allowing the Lord—her son—to live the life of an ascetic, she made the ultimate sacrifice. According to the Lord’s desire, she agreed to worship Him in separation. Sad thus experienced the highest, most esoteric relationship with the Lord, and Vaishnavas throughout the world seek to emulate her uncompromising devotion.

Vishnupriya

If Sachidevi was the perfect mother, Vishnupriya was the perfect wife. Lakshmi-devi, Sri Chaitanya’s first wife, died prematurely when she was bitten by a snake. Mother Sachi then pleaded with her divine son to remarry. He did, and the bride was Vishnupriya, daughter of the aristocratic Sanatana Mishra, a well-known politician.

When Sri Chaitanya soon left to pursue the life of an ascetic. Vishnupriya made the same commitment and sacrifice as did Sachidevi. Vishnupriya, however, also had to take care of Sachi, who was now becoming old and infirm.

Vishnupriya spent as much time with the name of God as with her beloved mother-in-law, and her reputation soon grew as a prominent ascetic in the Gaudiya Vaishnava line.

It is said that she would set aside one grain of rice each time she would chant the Hare Krishna mantra 108 times. When her utterances of the name were complete for a particular day, she would boil the accumulated rice and take that—and only that—as her daily meal.

As her austerities and exemplary behavior became known within the Vaishnava community, she was glorified for being the model of a chaste wife and also for being an ascetic of the mystical tradition. This made her a leader in the Vaishnava community.

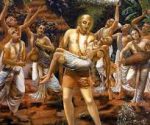

Jahnavadevi

Important women Vaishnavas soon took leading roles in Lord Chaitanya’s movement and even assumed the position of guru. One of the more prominent woman gurus was Jahnavadevi, wife of Nityananda Prabhu. Sri Chaitanya’s intimate associate and plenary expansion.

When Nityananda Prabhu married the two daughters of Sarakhala Suryadasa Pandita, the entire Vaishnava community was overcome with ecstasy, for the two girls were extremely pious and were known as great Vaishnavas. The younger wife, Vasudha, gave birth to two children: a boy, Virabhadra; and a girl, Gangadevi.

The young Vasudha soon passed away, however, and Jahnavadevi resolved to raise her sister’s children. In addition, she adopted a boy named Ramacandra. So Jahnavadevi spent much of her youth taking care of the three children, making sure they became great devotees.

Virabhadra, especially, grew to be a leader in the Vaishnava community, and when he accepted Jahnavadevi (his stepmother) as his guru, many prominent Vaishnavas did so as well.

Much of Jahnavadevi’s fame began as a result of her relationship with Nityananda Prabhu. But her activities soon revealed her greatness, and she was respected as a superlative Vaishnava on her own merit.

Her devotion to the famous Gopinatha Deity of Lord Krishna was so intense that this endeared her to the pious and impious alike. By her example she showed how to perform Deity worship and devote one’s life to spiritual pursuits. She even presided over huge Vaishnava festivals and gave initiation to men and women alike. It was Jahnavadevi, too, who had the insight to keep close contact with the Goswamis of Vrindavana, Lord Chaitanya’s chief followers there. In this way she sought to keep solidarity and unification between the branches of Gaudiya Vaishnavism in Bengal and in Vrindavana (Uttar Pradesh). The cohesive form of Gaudiya Vaishnavism that exists today is largely a result of her efforts.

One other phenomenon in the life of Jahnavadevi is pertinent to our discussion. Devotion to her mission and purpose became so strong that in her own lifetime a deity was made other, and this was to be placed alongside the Gopinatha Deity, who was the object of her veneration. A council was convened in Jaipur to decide the propriety of placing her deity next to Lord Gopinatha. The king of Jaipur and the assembled Vaishnavas decided unanimously that the deity should be established, and it was indeed placed next to Gopinatha within Jahnavadevi’s lifetime. Such a distinguished honor is uncommon among Vaishnava men and women alike.

Hemlata and Gangamata Goswami

In the next generation after Sri Chaitanya and Nityananda Prabhu (1600s or as late as the 1700s), many great female Vaishnavas followed the example of Jahnavadevi, two of the most prominent being Hemlata and Gangamata Goswami.

Not much is known about Hemlata Thakurani. She was the eldest daughter of Srinivasa Acarya and had many disciples, both men and women. She was a mystic of the highest order and developed a profound sense of love for God.

Gangamata Goswami, on the other hand, is written about quite often in the pages of Gaudiya Vaishnava history, especially in the historical records of the Nityananda-vamsha (from which she descends). Her guru was Haridasa Pandita, a disciple of Anantacarya, who was a follower of Jahnavadevi. In this way, her disciplic descent is traced to Nityananda Prabhu.

She was the daughter of King Naresha Narayana of Puntaya, of the Rajsahi district of Bengal. Unlike most great women Vaishnavas, even the mystics, Gangamata never married, and so she was given the title “Goswami” (“controller of the senses”) for her strict celibacy and profound wisdom. She did not take formal sannyasa (the renounced order of life in the Vedic social system), for she felt that the scriptures recommend sannyasa solely for men. But in spirit she adopted this path and so received the title “Goswami.”

The Deity of her heart was Madana Gopala, and she worshiped this form of Krishna with great devotion. In her youth, she studied in Vrindavana, and after many years she moved to Jagannatha Puri, where she lived at the ruins of what was formerly the house of the great scholar Sarvabhauma Bhattacarya. The Bhattacarya had been a prominent disciple of Sri Chaitanya, and although his house was now, almost two hundred years later, merely a run-down facsimile of its former self, Gangamata stayed there for the spiritual inspiration it bestowed.

At that house she found the sacred Damodara-shila (a Deity of Krishna in the form of a stone) once worshiped by Sarvabhauma Bhattacarya himself. She worshiped this Deity with the same intensity with which she had worshiped Madana Gopala in Vrindavana.

Mukundadeva Maharaja, the king of Puri once came to hear her recite Srimad-Bhagavatam, the sacred scripture of the Vaishnavas. He was so taken by her pure recitation and her elaborate explanations that he became her disciple and encouraged much of Puri to do the same. He financed a special temple to be built for her, and she became one of the prominent Vaishnavas of Orissa.

Conclusion

I have given only some preliminary examples of great women Vaishnavas. Nonetheless, we have seen examples of a great Vaishnava mother, a wife, mystics, celibates, and gurus. In short, the Vaishnava tradition has established precedents for women to assert themselves and distinguish themselves as outstanding Vaishnavas, both in traditional roles more commonly ascribed to women and in very independent roles that would perhaps be the envy of men.

Great women Vaishnavas have existed throughout the ages. and they have demonstrated that the qualities of leadership, scholarship, intelligence, wisdom, and devotion are affairs of the heart and mind, irrespective of sex.

Thank you very much. Are there any questions?

Question: I enjoyed the lecture very much. But I feel that feminists in general will be slighted. You’ve described the positive elements in the milieu with which you’re familiar—Vaishnavism, the Hare Krishna religion. But don’t the women of even that tradition feel exploited? Aren’t they still the product of a male-dominated society?

Satyaraja: There may very well be ample justification for the dissatisfaction of the feminists. Perhaps they have indeed been oppressed and exploited by a male-dominated society. Let us not forget, however, that it is a materialistic society in which this takes place. Exploitation is a symptom of selfishness. And selfishness is a symptom of the bodily concept of life. My contention is this: It is this bodily concept of life that is at the heart of materialistic thinking, and it is this rather than male domination that creates the exploitative mentality.

Q:I see.

S:Yes. If one identifies himself or herself as nothing more than a material body, the external self becomes of central interest—more important than the person within. Bodily differences are accentuated. Spiritual unity is overlooked. It would seem that the solution to exploitation—the major problem facing the feminists—is to obliterate materialism, not sexism. Sexist thinking is a symptom of the disease—the disease is materialism!

Q:OK, but the great women Vaishnavas whom you’ve mentioned and, more important, the rank-and-file women who follow Vedic culture—how have they risen beyond exploitation?

S:I’ve explained that already: by rising beyond the bodily concept of life. Men and women will rise beyond exploitation to the degree that they rise beyond the bodily concept and become established in the self—the actual, spiritual self.

Q:But devotees do not live in a vacuum! They may rise beyond the bodily concept, but they are still subjected to the exploitation of those who haven’t attained that level.

S:I see what you’re getting at. It’s actually a very good point On the other hand, a woman who pursues spirituality is protected by her discipline and the strictures of her religious tradition. She can never be exploited—even by members of society still on a lower level—because she never engages in sinful activity. Especially if she’s not engaging in illicit sex—who can exploit her?

Actually, she plays a leading and honored role within the social parameters of her family and community. In short, she avoids exploitation by being thoroughly devoted to God, Krishna, and she thus sees a spiritual equality, not a contrived material one. She knows that she is spiritually equal.

She feels that feminism betrays a narrow understanding of the purpose of existence, that it is predicated on competition between men and women. She knows that the only competition worth pursuing is between a person and his or her own conditioning. She has a role to play in her service to God, and it is this which concerns her—not some petty squabble about bodily differences.

So, in answer to your question, no, women who adhere to Vedic or Vaishnava practice do not feel exploited. To the degree that they are accomplished in Krishna conscious realization, they transcend the ability to be or feel exploited. In fact, they are unable to be exploited, because they give no room for exploitation. You must submit to materialistic life in order to be exploited. And a dedicated devotee will never do that.

Q:But do devotee women have equal positions? I mean, do they ever take service from men?

S:Not if they’re advanced. You see, according to Manu’s Dharma-shastra, there is a hierarchy, and in Vedic culture all members happily followed the system for social sanity. Everyone played his or her role. Everyone had an authority, and everyone was subordinate to someone else. In this way, one learned submission, culminating in submission to God. But the Vaishnava tradition added something special, an underlying and esoteric message of the scriptures: the true devotee wishes to be the servant of the servant of the servant of Krishna.

So, in actuality, you have material culture in reverse. Not “Who is serving me?” but “Who can I serve?” This is the devotees’ motto. So advanced devotees desire to be the menial servant not the master. And in this way they develop humility before God.

Incidentally, just so you don’t think I’m simply skirting the issue with some abstract philosophy. I will tell you that advanced devotees do accept service from novices, and in this way a novice can make advancement on the spiritual path. This holds true for both men and women. Many of the great women I mentioned in my lecture were gurus of both men and women and consequently accepted service. You see. Vaishnavism is not at all sexist Not really. But you must get beyond superficiality. In the ultimate analysis it is not gender but spiritual advancement that is the criterion.

Q:Do you believe that men and women are inherently different? OK. granted men and women are spiritually equal, but you alluded to bodily differences, and this is certainly true. What about more subtle qualities, though? How are we different on the subtle level? For instance, do you give credence to the theory about the right and left sides of the brain?*

S:Why not? I think that the research in this area leaves a great deal to be desired, but the basic premise is reasonable. In the Bhagavad-gita, for example, it is said that speech, memory, intelligence, faithfulness, and patience are feminine qualities. Is this sexist? These are admirable qualities. And this information is being confirmed by research into the right and left sides of the brain. There is scientific evidence that certain subtle functions of the brain are more characteristic of women than of men.

Q:Oh, come on! Men and women are perfectly equal, at least mentally. We have the same potential. Bodily differences I can give you. But subtle, mental differences? That’s going too far. It’s just an old wives’ tale. Or should I say an old men’s tale. [Laughter.]

S:I can appreciate your concern. To acknowledge mental and intellectual differences can lead to exploitation. But don’t misunderstand me. I am saying that our mental and intellectual faculties are equal, but that our mental and intellectual forte may vary from body to body. Just the forte. Just our point of emphasis. This can be and is heavily influenced by the kind of body we have.

I’m not merely giving you some dogmatic rhetoric. These ideas have been substantiated by some of the leading physicists and psychoanalysts in the world. For example, Dr. Georgene Seward, professor emeritus at Columbia University, has written two fascinating books on this subject: Sex and the Social Order and Psychotherapy and Culture Conflict. Have you seen these books?

Q: No.

S:I suggest you research your subject before you discuss it. These books were the landmark scientific publications that proved once and for all that “cerebral asymmetry” definitely exists between men and women. Dr. Seward, by the way, is a woman. So I don’t think you can call this “an old men’s tale.” [Laughter.]

You see, in our search for perfect egalitarianism, we are terribly afraid to admit that there are differences between sexes, or races, or nationalities, or living beings of any group at all. Somehow the possibility that physical or psychological differences of any sort exist strikes fear that this will be equated with superiority or inferiority of certain groups. But the denial that differences exist, whether biological or otherwise, only leads to absurdities. Indeed, it is the denial of our own humanity. We cannot respect differences among people unless we first admit them. This is not sexism or racism—it is merely common sense.

Bibliography

Bhakti-ratnakara, Narahari Cakravarti.

Chaitanya-bhagavata, Vrindavana dasa Thakura.

Chaitanya-caritamrita, Krishnadasa Kaviraja Goswami.

Prema-vilasa, Nityananda dasa.