The Life of Sri Jiva Goswami

Orinianlly published by The Harmonist

In honor of Sri Jiva Goswami’s tirobhava we offer the following article, which appears as chapter 1 of Swami Tripurari‘s Tattva Sandarbha: Sacred India’s Philosophy of Ecstacy and is entitled “Sri Jiva Jivanamrta.”

In honor of Sri Jiva Goswami’s tirobhava we offer the following article, which appears as chapter 1 of Swami Tripurari‘s Tattva Sandarbha: Sacred India’s Philosophy of Ecstacy and is entitled “Sri Jiva Jivanamrta.”

The principal source materials from which to gather biographical information on Jiva Goswami are Bhakti-ratnakara and Prema-vilasa. Both of these books chronicle events concerning the lives of Sri Caitanya and his followers. Prema-vilasa was written first, in the mid-16th century. Bhakti-ratnakara was written a century later. Prema-vilasa was authored by Nityananda dasa, a resident of Bengal. Narahari Cakravarti, who spent the better part of his life in Vrindavana, wrote Bhakti-ratnakara.

Scholars have questioned the accuracy of Prema-vilasa, and although practitioners accept both as authoritative, they seem to favor the details of accounts found in Bhakti-ratnakara. Time and distance inevitably distort accounts of events. These two books were written a century apart, one in Bengal and the other most probably hundreds of miles away in Vrindavana. The details of events vary considerably in these two texts, yet they both accurately represent the bhava, or ecstasy, of the events in question. Other than these two sources, the Caitanya-caritamrta also says a few words about Jiva Goswami, and Jiva Goswami sights his own genealogy in his Laghu-vaisnava-tosani.

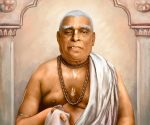

From the tradition’s point of view, Jiva Goswami’s life history is the unfolding of his spirituality from an unmanifest state to a manifest state within human society. Sri Jiva only appears to “become” enlightened, and through a mystic arrangement, he actually feels as though at one time he was not. He is considered to be internally possessed of the transcendental emotions (bhava) of a female lover (gopi) of the divine Krishna. Internally, he experienced Krishna’s celestial realm. Externally, he appeared as a practitioner of extreme renunciation and devotion. His life thus instructs us that the highest love of Krishna, often portrayed as an unmarried girl’s love for a young man, has little if anything in common with the affairs of unmarried young couples of this world. Whereas love of Krishna is free from selfish desire, mundane love is based upon it.

We know that Jiva Goswami was the son of Vallabha. His ancestry was South Indian. Hailing from Karnataka, they were Sarasvata brahmanas. He was born in Ramakeli, West Bengal in 1513 c.e. Muslims ruled West Bengal at the time of Sri Jiva’s appearance, and it came to pass that his father and two uncles were employed by the governor, Nawab Hussain Shah. They held positions with influence similar to that of cabinet members of a president. Well-educated, cultured, pious, and wealthy, they led comfortable lives.

Although at that time there was relatively peaceful coexistence in Bengal between the Hindus and Muslims, when the three brothers accepted employment in the Muslim government, they became social outcasts of the Hindu religious society. They were accepted, however, and in no small measure, by Sri Caitanya, an avatara and God-intoxicated devotee at once, as well as a religious and social reformer. By that time, Sri Caitanya had created quite a stir in West Bengal and Jagannatha Puri. Taking to the streets with cymbals and drums, he alienated both orthodox Muslims and Hindus, but collected a mass of followers from the ranks of each sect. His religion: passionate love of God. His method: chanting the names of God. While disturbing those entrenched in the formalities of a particular religious conceptual framework, he afforded those who followed him spiritual experience beyond religious formalities. Among the latter were Sri Jiva’s father and uncles, whom he would eventually follow.

Sri Jiva’s father and uncles had heard of Sri Caitanya and corresponded with him. When Sri Caitanya returned to Bengal from Puri, the news of his conversions there were rippling throughout India. He visited the home of these three Sarasvata brahmanas, the home in which Sri Jiva was a tender youth. What were the names of Sri Jiva’s uncles? We know only what names they received from Sri Caitanya during this visit, and Jiva, having received this name subsequently from one of his uncles, is known only as such. Sri Caitanya named Sri Jiva’s two uncles Sanatana and Rupa and changed his father’s name to Anupama. From this we can conclude that the three became Sri Caitanya’s disciples.

Shortly after being accepted by Sri Caitanya, the brothers left family life and entered the life of devotion and renunciation, leaving Sri Jiva behind. Yet they left with Sri Jiva the spirit of their vision. The boy took note of how his elders left a life of material opulence for one ostensibly of begging. They left aristocratic status and wandered the breadth of India barefoot, clad only in loincloths, with water pots and rosaries as their only possessions. Sometimes they ate, more often they went without. Their renunciation, however, was merely a by-product of their love-intoxicated state. They fasted not so much as a conscious austerity, but as a result of their absorption in divine love—they forgot to eat and to sleep as well. Mendicants they appeared to be, but ordinary mendicants they were not.

Government employment may have ostracized them from the religious Hindu community, but it did not make them poor. They enjoyed considerable wealth in government service. Yet it was apparent to the young Jiva that they had not left religion for money, nor in joining Sri Caitanya, money for mere religion. Theirs was a spiritual vision that transcended not only dharma (religion) and artha (wealth), but kama (material enjoyment) and even moksa (liberation). This was the ideal of Sri Caitanya: Krishna prema, passionate love of God that belittles even salvation from the cycle birth and death (samsara). Sri Jiva glimpsed the effects of this love in Sri Caitanya and its influence that overflowed onto his elders. They embraced the life of devotion after meeting merely once with Sri Caitanya, his love-intoxicated state was so contagious. With a penetrating eye of introspection, Sri Jiva analyzed the significance of his father and uncles’ departure from home and chose to follow in their footsteps. Later, with the same penetrating vision, his eyes anointed with the salve of love (prema), he would write extensively on the philosophy of the love and ecstasy that Sri Caitanya embodied.

Sri Jiva was more than a handsome youth. His bodily features were those of a maha-purusa, or great personality (by spiritual standards). According to the Samudrika, “There are thirty-two bodily symptoms of a great personality: five of his bodily parts are large, five fine, seven reddish, six raised, three small, three broad, and three grave.”

He was young when he left home. While still an adolescent, he questioned his mother about the life of renunciation and devotion. His mother dismissed his inquiry as no more than childhood infatuation with a life of material hardship and spiritual pursuit. Sri Jiva surprised her by appearing before her in mendicant dress, having learned from her that such attire was requisite. More so she must have been astonished when his apparent youthful infatuation for the dress of devotion, a mere monk’s robe and shaven head, proved to be mature participation in spiritual emotion.

After leaving home, Sri Jiva went to Navadwip of West Bengal. It was here that Sri Caitanya had appeared. In Navadwip, then a seat of learning, Sri Caitanya began his movement. Shortly after he had begun to manifest his ecstasy, he was joined by Prabhu Nityananda, who is considered to be his “other self.” Sri Jiva met Nityananda and was personally instructed by him in the esoteric doctrines of what would become known (chiefly through the writing of Jiva Goswami and his uncles) as Gaudiya Vaisnavism.

On the advice of Nityananda, Sri Jiva traveled from Navadwip to Benares enroute to Vrindavana. There he studied under the tutelage of the famous Madhusudana Vacaspati (not to be confused with Madhusudana Saraswati, an Advaitin). Madhusudana Vacaspati was related to the renowned Sarvabhauma Bhattacarya. He must have learned Vedanta from Sarvabhauma after the Bhattacarya himself learned Vedanta from Sri Caitanya in the midst of the Bhattacarya’s dramatic conversion. Benares was immersed in an atmosphere of learning. There Sri Jiva learned Vedanta and numerous other branches of knowledge in a very short time. It is apparent from his books that he was a good student, well versed in the philosophies of Vaisesika, Nyaya, Sankya, Yoga, Purva-mimamsa, and Uttara-mimamsa. This comprehensive knowledge is a characteristic of a maha-bhagavata, or superlative devotee.

From Benares, he continued on to Vrindavana. By the time he arrived there his father had died prematurely. In Vrindavana, he took shelter of his uncles, Rupa and Sanatana Goswamis, accepting spiritual initiation from Sri Rupa. Presumably it was from Sri Rupa that Jiva Goswami received the name Jiva, upon being initiated into the Krishna mantra. The title Goswami is not hereditary, rather it is conferred upon one who has conquered over his mind and senses.

Sri Rupa, Sanatana, and Jiva were three of those known as the Six Goswamis. Together with these three lived Gopala Bhatta, Raghunatha Bhatta, and Raghunatha dasa Goswamis. Amongst them, Sri Jiva was the youngest and most prolific. He was a perfect disciple of Rupa Goswami and certainly qualified to initiate others, yet it is questionable as to whether or not he personally initiated any disciples, although many considered themselves his disciples and he appears to have addressed some devotees as such.

Sri Rupa and Sanatana did not accept disciples, Sri Jiva their nephew a lone exception. The reason for this was not their lack of qualification. It seems that the socioreligious climate of the times was respected by the Goswamis. They reformed the society yet remained within existing socioreligious parameters, having assessed that which they had to contend with in order to successfully establish an organized systematic school of thought (sampradaya) centered around the ecstasy of Sri Caitanya. Thus for some time students desiring initiation were regularly referred to Gopala Bhatta Goswami, who hailed from a prestigious South Indian brahmana family. If Sri Jiva did not personally initiate, it was in pursuance of this strategy. The sampradaya’s next generation appears to have been less concerned with disturbing the socioreligious climate. By this time the sampradaya was better established, with a literary legacy of considerable size and temples built with the patronage of the rajas. Two of the sampradaya’s leading members, Narottama dasa and Syamananda, were not from brahmana families, and Syamananda from the lowest caste (sudra), yet they did initiate widely while Sri Jiva was still alive. Thus the policy of Sri Rupa and Sanatana, one probably followed by Sri Jiva as well, was based not upon devotional conclusions of the sampradaya, but upon consideration of the social climate of the day, as well as the humility of the three Goswamis.

Sri Jiva devotedly served his seniors and continued to live in Vrindavana, eventually becoming the spiritual guide for all of the followers of Sri Caitanya until the end of the sixteenth century. He was the ultimate authority in all esoteric and practical issues concerning the culture of spiritual love. After the departure of Sri Rupa and Sanatana, he served the community in this capacity even in the presence of others senior to himself.

His life in Vrindavana was that of extreme renunciation and devotion. He wore only the traditional loincloth and accepted many hardships in the service of the absolute. At the same time, he was intimately involved in excavating the places of Krishna’s pastimes and building temples for the deities of Radha-Krishna and Sri Caitanya. Fabulous temples of architectural wonder were arranged for the deities, yet Sri Jiva himself slept beneath the trees. The Govindaji Mandir in particular is an extraordinary blend of architectural styles that reflects the prominent religious influences of the time, built as a monument to the deity that in Sri Jiva’s mind represented transcendence of religious convention. That Sri Jiva was intimately involved in its fourteen years of construction is evidenced by his “Govinda mandir-astakam“, an eight verse tribute to this temple and its patrons.

At one point, the powerful emperor Akbar came to Vrindavana with the hope of meeting this extraordinary ascetic. Akbar was a man of enormous wealth and influence, yet he was humbled to hear of the spirituality of Sri Jiva and his elders. He patronized Sri Jiva to the extent of removing obstacles that impeded the development of Vrindavana by the rajas, who subscribed to the religion of love explained by and embodied in Jiva Goswami.

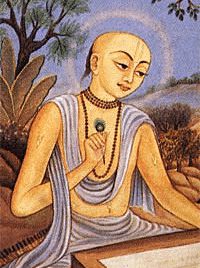

More than twenty-five books are attributed to Sri Jiva. The list of these twenty-five found in Bhakti-ratnakara ends with “etcetera.” Caitanya-caritamrta credits him with writing more than four hundred thousand verses. If this is accurate, it makes Sri Jiva second only to Vyasa in authoring Sanskrit verses concerning the nature of the absolute truth. The tradition holds that whatever he wrote was first fully manifest in his mind and once he committed a thought to writing he never changed it.

Of all of his books, Sat-sandarbha is the most famous. In this sixfold treatise, he manifests his opulence of superhuman command over the enormous body of India’s sacred Vedic and supplementary Vedic literature. From the Vedas, Upanishads, Puranas, Itihasas, and the epic Mahabharata to the Tantras and agamas, there seems not a page unturned by Sri Jiva. His comprehension of their contents makes it appear almost as though he wrote them himself. Studying Sat-sandarbha, one is held spellbound by this opulence alone, dumbfounded by Sri Jiva’s scriptural command, what to speak of the realization he so kindly shares therein. Sat-sandarbha serves as the philosophical foundation for the ecstasy and love that Sri Caitanya embodied and Sri Jiva experienced so deeply.

In Sat-sandarbha, Sri Jiva argues persuasively that the ecstasy of Sri Caitanya is that which the entirety of Vedic India’s vast sacred literary heritage is pointing to. To his arguments and conclusions, there are no doubt counterarguments, as all logic is inconclusive and scripture lends to innumerable interpretations. Yet it is the charm of his conclusions—Krishna lila—that is difficult to match. A more endearing conception of the absolute, reasonably and eloquently articulated and well supported by a sacred literary heritage is, if in existence, yet to express itself.

Sri Jiva Goswami is one of the greatest religious philosophers in history. His spiritual lifestyle is instructive to us as well. It would be difficult to find a person as intelligent as Sri Jiva, who at the same time thought so little of intelligence. He used his intellect to argue on behalf of the eternal soul, and more, its emotional potential in transcendence. While doing so, his life’s example teaches us that there is indeed firm ground to stand on beneath the soft surface of the ground of our material experience. That ground of being, while firm, is moving. Its movements, however, are not cause for concern for those who stand upon it. This is so because, to begin with, we are that ground. But in Sri Jiva’s eyes, there is more to tell, much more that makes for a Vedanta of aesthetics. Realizing ourselves to be consciousness is to stand at the door of transcendence. Sri Jiva opens the door to a life in transcendence culminating in the circular love dance (rasa) of Sri Sri Radha-Krishna, synonymous with the ecstatic chanting and dancing of Sri Caitanya.

On the ground of consciousness, Sri Jiva has crafted a deity out of the same material, his chisel the Bhagavata Purana. His deity is dark and handsome and never alone, standing eternally in the embrace of his feminine counterwhole. He rules over all by the force of affection and beauty. He is a deity more human than transcendent, more transcendent than human. Sri Jiva has built a temple for this deity, and that too is made out of the ground of being, pure nondual consciousness. It is spacious and inviting in the most charming sense. Call this deity Krishna, his feminine counterwhole Radha, and be done with a life of illusory happiness and empty promises of love. Calling their names, Sri Jiva turned his back on this illusory world to tell us of another, which, as it turns out, is no more than this world when viewed through eyes anointed with divine love.