Human life begins in bright flash of light as a sperm meets an egg

Human life begins in bright flash of light as a sperm meets an egg, scientists have shown for the first time, after capturing the astonishing ‘fireworks’ on film.

Human life begins in bright flash of light as a sperm meets an egg, scientists have shown for the first time, after capturing the astonishing ‘fireworks’ on film.

An explosion of tiny sparks erupts from the egg at the exact moment of conception.

Scientists had seen the phenomenon occur in other animals but it is the first time is has been also shown to happen in humans.

“To see the zinc radiate out in a burst from each human egg was breathtaking.”

Professor Teresa Woodruff, Northwestern University

Not only is it an incredible spectacle, highlighting the very moment that a new life begins, the size of the flash can be used to determine the quality of the fertilised egg.

Researchers from Northwestern University, in Chicago, noticed that some of the eggs burn brighter than others, showing that they are more likely to produce a healthy baby.

The discovery could help fertility doctors pick the best fertilised eggs to transfer during in vitro fertilisation (IVF).

“It was remarkable,” said Professor Teresa Woodruff, one of the study’s two senior authors and an expert in ovarian biology at Northwestern.

“We discovered the zinc spark just five years ago in the mouse, and to see the zinc radiate out in a burst from each human egg was breathtaking.

“This means if you can look at the zinc spark at the time of fertilization, you will know immediately which eggs are the good ones to transfer in in vitro fertilization.

“It’s a way of sorting egg quality in a way we’ve never been able to assess before. “All of biology starts at the time of fertilization, yet we know next to nothing about the events that occur in the human.”

Currently around 50 per cent of fertilised eggs do not develop properly and experts believe that faulty genetic code could be responsible.

Some clinics take videos of the egg developing to try pick up problems early, while others check for genetic mutations, but that is an invasive procedure which can damage the tiny egg. Often it is just down to a clinician decided which eggs look the healthiest.

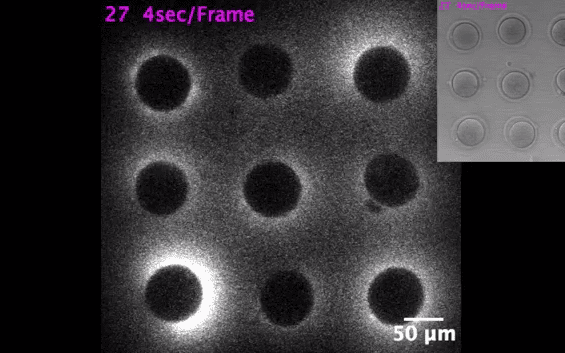

But the new findings could give and extra indication that an egg is flourishing. A video of nine human eggs coming into contact with sperm enzyme showed two flashed much brighter than the rest.

“This is an important discovery because it may give us a non-invasive and easily visible way to assess the health of an egg and eventually an embryo before implantation,” said co-author Dr Eve Feinberg, who took care of the patients who provided eggs for the basic science study and collaborated with the research team.

“There are no tools currently available that tell us if it’s a good quality egg. Often we don’t know whether the egg or embryo is truly viable until we see if a pregnancy ensues.

“That’s the reason this is so transformative. If we have the ability up front to see what is a good egg and what’s not, it will help us know which embryo to transfer, avoid a lot of heartache and achieve pregnancy much more quickly.”

The bright flash occurs because when sperm enters an egg it leads to a surge of calcium which triggers the release of zinc from the egg. As the zinc shoots out, it binds to small molecules which emit a fluorescence which can be picked up by camera microscopes.

Over the last six years this team has shown that zinc controls the decision to grow and change into a completely new genetic organism.

In the experiment, scientists use sperm enzyme rather than actual sperm to show what happens at the moment of conception.

“These fluorescence microscopy studies establish that the zinc spark occurs in human egg biology, and that can be observed outside of the cell,” said Professor Tom O’Halloran, a co-senior author.

In a companion paper published in Scientific Reports on March 18, a zinc spark is shown at the precise time a sperm enters a mouse egg.

This discovery was made by Nan Zhang, a postdoctoral fellow at Northwestern. Little is known about the events that occur at the time of fertilization, because it is difficult to capture the precise time of sperm entry.

The study will be published April 26 in Scientific Reports.